New England Botanic Garden’s Historic Apple Orchard

Located along New England Botanic Garden’s entry drive, the Frank L. Harrington Orchard preserves a historic collection of 119 heirloom apples represented by 268 trees. The collection got its start during the Great Depression with Worcester County Horticultural Society (WCHS) trustee Stearns Lothrop Davenport (1885–1973). Also known as heritage apples, heirloom varieties have been passed down over generations and are celebrated for their diversity of taste, color, texture, and size. The Harrington Orchard features many old and uncommon apples, a number of which originated in Massachusetts. It also includes several varieties that are extremely rare.

The Harrington Orchard serves as a living museum chronicling the region’s agricultural history. It also represents the Garden’s commitment to environmental stewardship and the protection of natural resources. As apples cannot be held in seed banks, living collections provide the only means for preserving the genetic material that makes heirloom apple varieties unique. In the age of climate change, agricultural biodiversity has never been more important. If heirloom varieties are lost, not only do we lose a piece of history, but also any undiscovered genetic traits, such as novel resistances to drought, pests, and diseases, that might benefit future scientific research.

The Harrington Orchard is named for fruit tree enthusiast and longtime WCHS supporter, Frank L. Harrington. It was dedicated in 1990 by his sons, Frank Harrington, Jr. and George Harrington. In 2024, a generous gift by George and his wife Diantha Harrington was added to the Orchard’s endowment to support the long-term care of the trees and expand educational initiatives that build public awareness of the historic significance and scientific importance of this special collection.

The Orchard in the News

- The real Johnny Appleseed: A legacy evolved and honored, Chronicle, September 2024 (PDF)

- Historic apples get a new start, with Mark Richardson, A Way to Garden, September 2022 (PDF)

- Replanting the Orchard, Grow With Us (pg. 2), 2021

- Fire Blight spreads northwwards, threatening apple orchards, New York Times, December 2019 (PDF)

Heirloom apples, also called heritage apples, are apple varieties that are increasingly rare in today’s supermarkets. Over the decades, with the onset of large-scale agriculture, apples have been selected for commercially desirable traits such as the ability to travel well. As a result, a small number of apples now dominate the market. What has been lost is variety and genetic diversity. Heirloom orchards showcase the art and science of fruit cultivation, preserving varieties that were selected and passed down over generations.

Preserving heirloom apples in living collections is important because apple varieties don’t “come true,” as horticulturists say, when grown from seed. This means that you can’t collect a seed from the ‘Gala’ apple you’re eating and expect it to grow another apple that looks and tastes like your ‘Gala.’ The process of pollination introduces genetic material from other apples, so any offspring grown from seed will be different from the parent tree. To maintain the traits

of a specific apple variety — that is, to grow another ‘Gala’ — trees must be asexually or clonally propagated through a process known as grafting. Through grafting, scionwood, shoot cuttings taken from new growth on existing trees, is carefully spliced into the rootstock of another tree. This means the apples we know and love today are derived from the same trees selected years ago and all the trees of that variety have come from scionwood bought, sold, and traded throughout the decades.

During the Great Depression, Stearns Lothrop Davenport (1885–1973), a WCHS trustee working for the Massachusetts Department of Food and Agriculture, directed a Work Progress Administration (WPA) project charged with felling abandoned apple trees that were harboring insects and diseases and negatively affecting commercial orchards. In the course of this work, Davenport began to worry he might be turning trees that represented the last varieties of some apples into firewood, losing unique qualities, unusual histories, and genetic material forever. He began grafting scionwood, shoot cuttings taken from the rare varieties he encountered, to trees in his own orchard at Creeper Hill in North Grafton, Massachusetts.

Russell Powell, author of Apples of New England, says Davenport may have done more to preserve heirloom apple varieties than anyone in the 20th century. Davenport worked with researchers at UMass Amherst to develop a list of 100 varieties they believed needed saving and he spent much of his life sleuthing around New England, the U.S., and beyond to find these varieties and add them to his collection. He also shipped more than 12,000 scions to interested growers around the world from the orchard he started in the 1930s.

As secretary of WCHS, which had a long history of celebrating the region’s rich diversity of agricultural produce at regular expositions, Davenport worked to maintain and expand his experimental preservation orchard project. He passed in 1973, and because WCHS did not own land at the time, the Society collaborated with Old Sturbridge Village to ensure the collection was preserved. The collection remained at Old Sturbridge Village for decades. Scionwood was gathered for distribution each spring and apples were harvested for exhibitions and cider making each fall.

In 1986, WCHS purchased Tower Hill Farm in Boylston, Massachusetts, with the purpose of building a botanic garden for the public to enjoy. The property had served as a dairy farm for generations and had plenty of space to host Davenport’s heirloom apple collection. Staff and volunteers, led by WCHS trustee Gladys Bozenhard, harvested scionwood from the Old Sturbridge Village trees, grafted the small branches to semi-dwarf rootstock, and cared for the saplings in a nursery onsite until they were ready to be planted.

Over the years, the Garden grew Davenport’s collection and used it as a source of scionwood for people around the world interested in uncommon apples. Garden staff distributed scionwood through a mail order program, harvested apples for fall exhibitions, and sold some apples to local brewers to make cider. Tours provided opportunities for the public to learn about the fascinating histories of heirloom apples and taste interesting varieties they’d likely never encountered before.

Today, the Frank L. Harrington Orchard is in its newest chapter following a multi-year restoration project that involved replanting the entire orchard. The restoration began in 2018 and was led by Director of Horticulture, Mark Richardson. The trees in the orchard were reaching the ends of their intended lifespans. Semi-dwarf apples live for only about 20 years. Apples planted using standard rootstock can live for more than 100 years. The collection was also threatened by a widespread outbreak of fire blight.

Fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) is an aggressive bacterial disease that affects plants in the Rosaceae family. Historically associated with the southern region of North America, fire blight is increasingly affecting New England apple orchards as a result of climate change. When springtime weather conditions are moist and temperatures reach above 70 degrees, bacterium enter the vascular systems of plants, often spreading blossom to blossom by wind, heavy rainfall, or flower visitors including pollinators. Affected trees develop a scorched appearance along their branches.

There is no cure for fire blight. Even with intensive treatments, some of which can make fruits inedible, trees may still succumb to the blight. Without intervention, Davenport’s historic collection could have been lost.

Restoration Timeline

- FEBRUARY 2019: Scionwood collection and grafting begins

To ensure all varieties in the collection would be preserved, scionwood was carefully taken from each of the old trees and grafted onto fire blight resistant rootstocks identified in the industry as M111, G890, and Antonovka. With few exceptions, the scionwood used for the orchard restoration came from trees onsite. - 2019 – 2020: Grafted trees grow in a nursery in Maine

To propagate the orchard, the Garden sought the expertise of John Bunker, orchardist and founder of Fedco Trees, a specialty nursery co-op in Clinton, Maine. Bunker assisted in grafting all 119 apple varieties and helped coordinate tree care over two growing seasons at a nursery contracted by Fedco. - FALL 2019: Apple trees are completely removed from the Orchard

To restore the orchard, the Garden had to completely remove all the old, diseased trees. Before new trees could go into the ground, soil was tilled and compost added to create a healthy and productive root zone. - SPRING 2021: Saplings are planted

With the help of community volunteers, apple tree saplings were planted according to an updated layout that expanded the collection’s footprint. Trees on standard rootstocks that can grow as high as 40 feet and live up to 150 years have been planted along the Garden’s driveway. As these trees grow and mature, they’ll welcome generations of guests to the Garden. - SUMMER 2022: Irrigation is completed

Each new tree was outfitted with its own drip irrigation emitter, allowing Garden staff and volunteers to efficiently deliver water to feed the development of a healthy root system without encouraging disease. This system helps establish young saplings and provides supplemental water during drought. - 2022 – PRESENT: Ongoing maintenance and care continues

Using fire blight resistant rootstock helps defend against disease, but the approach isn’t foolproof. The Garden continues to closely monitor the orchard for presence of fire blight and follows a careful preventative integrated pest management program to keep it at bay. Other regular orchard maintenance includes pruning, fertilizing, and managing the meadow under the trees. The meadow replaced turfgrass for added ecological benefit.

The Orchard restoration that took place between 2018 and 2022, along with advances in DNA technology, created new opportunities to learn more about the apple varieties in the Garden’s collection. In the summer of 2023, researchers from Washington State University’s Apple Genome Project visited the Orchard. The project aims to create a genetic fingerprint of every apple on the planet. Using DNA from leaf samples, scientists can establish an apple variety’s pedigree, or its relationship to other known apple varieties.

Leaf samples were collected from all of the Orchard’s trees, and DNA testing has revealed that some of the Garden’s apples are exceptionally rare — the only examples currently in the DNA database — and a couple aren’t what they were believed to be. Ongoing collaborations with partners at RegisTREE of North America, an international tree ID project, the Maine Heritage Orchard, and College of the Atlantic continue to deepen the Garden’s understanding of its apples and their history. This knowledge informs collection management and demonstrates how heirloom orchards can help facilitate research, ultimately strengthening preservation efforts occurring locally, nationally, and beyond.

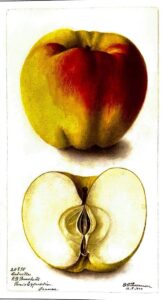

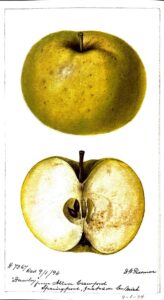

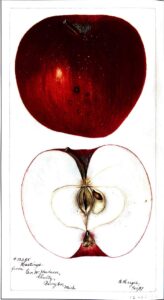

The Harrington orchard includes 119 heirloom apple varieties, also known as heritage apples. These apples, handed down over generations, were selected and grown for a diverse array of traits such as taste, harvest time, and purpose. Before DNA testing was available to help identify apple varieties, experts relied on pomological watercolors like those below. (Daniel J. Bussey, The Illustrated History of Apples in the United States and Canada, 2016)).

Apples in the Garden’s collection include ‘Early Joe’ (c. 1800) a variety that could be harvested, as the name suggests, early in the season, ‘American Pippin’ (c. 1817), a hard cider apple, the ‘Lady’ (c. 1628) and ‘Hawley’ (c. 1750), both considered good dessert apples, and the ‘Opalescent’ (c. 1899), an apple from Michigan that was prized for all purposes. Some apples in the collection, like ‘Sutton’ (c. 1848) and ‘Hubbardston’ (c. 1832), carry names of Central Massachusetts towns where they originated. The oldest apple in the collection is the ‘Calville Blanc,’ an apple that traces its roots to France in 1598. The ‘Calville Blanc,’ a greenish yellow dessert apple with ridges and a light red blush, is known for its appearance in the still life painting “Apples and Grapes” by by Claude Monet. The collection also includes the ‘Davey,’ a variety Stearns Lothrop Davenport selected himself for traits he thought worthy of reproducing in 1928.

Full apple list coming soon!

Images from The Illustrated History of Apples in the United States and Canada by Daniel J. Bussey